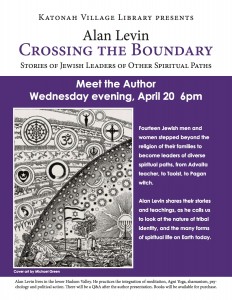

THIS IS A REQUEST FOR HELP: If you already know the value of my book, Crossing the Boundary: Stories of Jewish Leaders of Other Spiritual Paths, please help me spread the message to more people. If you have already read it, you know that it offers, through the lens of Jewish boundary-crossers, universal wisdom teachings that move us towards a more compassionate sense of who we are and what we are doing here. At this time of intensifying fear-based tribalism, I am hopeful this book is good medicine.

I would greatly appreciate it if you would please forward this message to two or three friends with a word about the value of the book. If you’d like to buy a copy for yourself or a gift for a friend, that would be wonderful. Please note the discount rate through the end of the year. Signed copies of the book can be purchased at www.CrossingTheBoundary.org. Great gift for Christmas, Chanukah, Solstice or just for a plain gift of love.

I continue to expand on the theme of crossing boundaries through this blog and I hope you enjoy and find value in the post below.

Special offer through the end of the year –

$20 plus shipping.

Purchase Book here: www.CrossingTheBoundary.org

Peace and blessings,

Alan Levin

It came as a surprise to some, (but certainly not all) readers of Crossing the Boundary to find that most of the fourteen spiritual teachers in the book (plus myself) had significant experiences with psychedelics that began or enhanced their spiritual journey. Several speak of their ongoing use of such substances in sacramental ways as part of their spiritual practice.

Nothing in this message is meant to encourage anyone to take psychedelics. They are, after all, illegal. I write this only to open the discussion to what stands out so strongly to many readers of Crossing the Boundary and yet is something I chose not to emphasize in previous publicity descriptions of the book. I confess this may have been due to my own shyness with the controversial nature of the subject. But, it seems the cat is coming out of the bag, or a better way to say it is: the mushroom is popping up out of its hidden underground mycelial web.

So many books and articles have been written about psychedelics that it amazes me that most Americans are still unaware of them as serious tools for consciousness expansion and spiritual development. Recent articles in the New York Times and Scientific American are reporting on the very promising research being done with psychedelic substances for treatments of PTSD, depression, addiction, and quality of life for people with cancer. Often overlooked, though hiding in plain sight, is the fact that accompanying the positive therapeutic results of any of these treatments, there is the frequent, (if not close to universal) report of spiritual, religious or mystical experiences in the treatment sessions. Many report that it is that experience that provided the force of the therapy.

Indeed, while many people continue to take psychedelics for recreational purposes, enjoying the many sensory and emotional pleasures of the experience, a strong subset have continued the deeper, psychologically mind-expanding and spiritual explorations that psychedelics can enhance. Folks involved in this work now generally refer to the substances themselves as “medicines” and use the term entheogen (bringing forth the divine from within) rather than the often demonized or trivialized term, psychedelic (suggesting for many people that you see groovy patterns of color moving around). It’s quite clear from some of the accounts of those I interviewed for Crossing the Boundary, that entheogens often provide, in the right setting, the deepest of openings to whatever it is we call higher consciousness, Oneness, Spirit, the Divine, or God.

Some will still argue that the experience people have with psychedelics/entheogens is not a “valid” spiritual experience because it is induced by a drug. This notion runs counter to the statements of the many spiritual teachers and students who have had experiences of transcendant and mystical states with both entheogens and long periods of meditation or prayer and testify to their being essentially equivalent.

There is also the very interesting study that followed up on what is known as the Harvard “Good Friday Experiment” of 1962. For his PhD in Religion, Walter Pahnke led a controlled experiment to determine whether psilocybin generated genuine mystical experiences. Briefly, Pahnke administered both psilocybin and a placebo to a group of 20 divinity students and recorded their reports. The findings were that most of those who took the psilocybin reported religious or mystical experiences whereas there were none in the control group. The follow-up study, headed by Rick Doblin of MAPS, (The Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies) was done 40 years later. Doblin was able to find many of the original “Good Friday” participants (many having become religious leaders) who all reported the 1962 experience was their first true religious experience and was as “valid” as any later experience. For a fascinating detailed account of this study, see: here.

An even more significant validation of the link between spirituality and entheogenic plants and substances is the testimony of the many spiritual teachers who acknowledge with deep respect the positive effects such experiences had on their journey. Among these are Aldous Huxley, Alan Watts, Huston Smith, Ram Dass, Stanislav Grof, Ralph Metzner, Jack Kornfield, Bill Wilson (founder of A.A.), and a very long list could follow. See Zig Zag Zen for some excellent discussion about this from a wide range of teachers as well as art by Alex and Allyson Grey (Allyson is featured in Crossing the Boundary). As mentioned above, almost every one of the well respected teachers in Crossing the Boundary attribute entheogenic experiences as a primary key to their opening to deep spiritual practice.

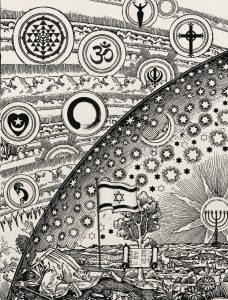

The depiction in the alchemical drawing used as a basis for the cover of my book can easily be seen as the dissolving or peaking through the boundary of one’s cultural conditioning to a larger universe, the expansion of consciousness. (The original is above and the one adapted by artist, Michael Green, for the “Jewish” version is below.) We all may ask, what lies beyond the current boundaries of our belief systems and mind-habits and how can we open our hearts and minds to a larger sense of ourselves.

It certainly seems clear that we are at a critical time in the evolution of human consciousness. If, as so much evidence indicates, people are moved to greater states of compassion, unity, joy and transcendence through ingestion of these substances in carefully prepared settings, then shouldn’t getting them out of the locked vaults of government prohibition be a primary goal for us. It behooves us to support research into the appropriate uses and potential dangers and learn from the indigenous societies that have incorporated their use into their sacred ceremonies.

I offer the links below to offer just a few of the many significant books and resources for understanding the subject of psycho-spiritual growth, healing and entheogens:

10 minute video of Stan Grof describing his first LSD experience Dr. Grof, it is safe to say, is the most respected researcher of psychedelics and consciousness studies.

Green Earth Foundation: Here you can find Ralph Metzner’s many books on the subject which are a treasure trove of information about the different substances used for psycho-spiritual growth and include his razor sharp insights into these experiences and their meaning.

Psychedelic Gospels (research on the use of psychedelics in early Christianity).

The Ketamine Papers (accounts of the use of ketamine for healing and transformation).